Pivoting Our Irrigation Strategy

by William Layton

Drive through farmland during the summer and you will notice enormous steel tower “irrigation pivots” (or what people here call a “Delmarva carwash”) stationed in the fields. These large crop sprinklers have been shown to be profitable by creating bigger, heartier crops.

Drive through farmland during the summer and you will notice enormous steel tower “irrigation pivots” (or what people here call a “Delmarva carwash”) stationed in the fields. These large crop sprinklers have been shown to be profitable by creating bigger, heartier crops.

The flipside is that they can be expensive to run. Each unit can pump up to 1200 gallons-per-minute across a field. That is a tremendous amount of water, and while we seem to have an endless supply of around us on the Peninsula, that’s not always the case.

When you water a houseplant, it’s easy to touch the soil and know if the plant needs water. It is much harder to look at an entire field and know if it is too dry. Most farmers (including me, up to this point) err on the side of having plenty of water on their crops, which can waste ground water, staff-hours and diesel fuel.

At Lazy Day Farms and Layton’s Chance Vineyard & Winery, we are working with a new technology to help us run our irrigation pivots more efficiently: soil moisture probes. These probes, which are installed after planting (and then removed after the harvest for winter), measure the amount of moisture in the soil at 6-, 12-, and 18-inches deep.

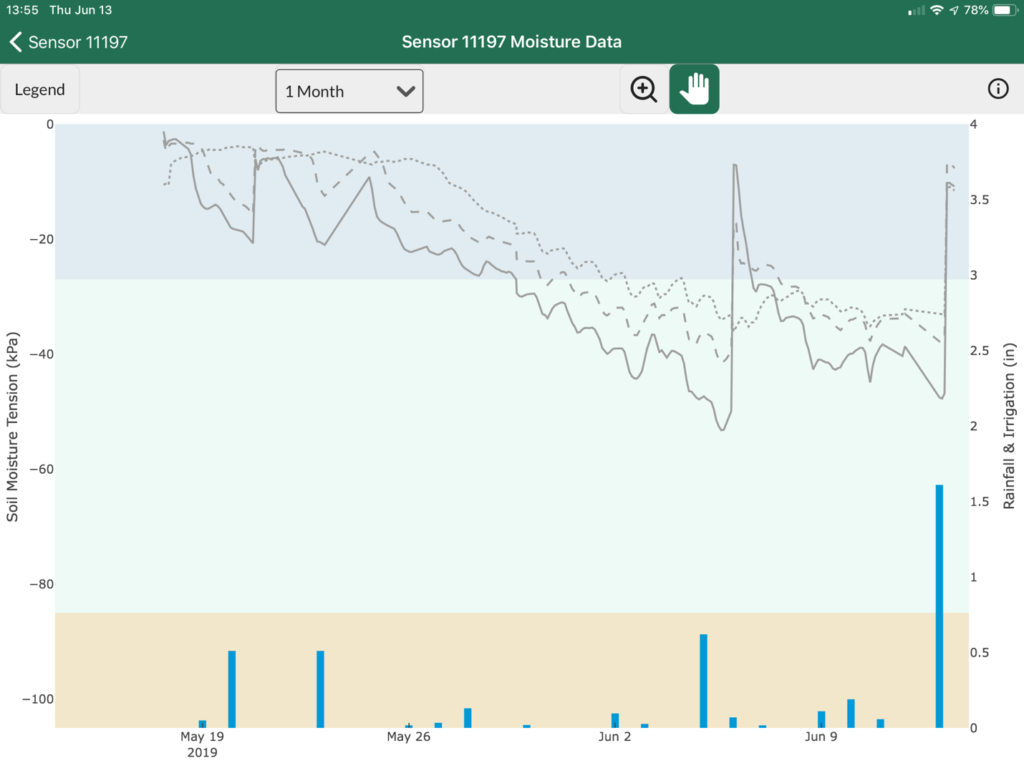

The sensors on the probes communicate moisture levels – not only on the surface, but a foot or more down at the roots. The results are displayed on a bar graph (see our example, below) that shows the moisture levels every hour throughout the day.

Water, more than any other natural resource, is the key to crop success. Managing it responsibly is one of our most important values on the farm. Especially in this unrelenting high heat, these sensors are making a difference to the crop and to the land.

Water, more than any other natural resource, is the key to crop success. Managing it responsibly is one of our most important values on the farm. Especially in this unrelenting high heat, these sensors are making a difference to the crop and to the land.

For farmers, there is still the question of where on the graph you should start irrigation, but making fact-based decisions – with this data and our own years of experience – will help us improve land, water and crop management.

This chart shows how much water has fallen (blue bars), by date (across the bottom), and corresponding moisture probe readings (from the top.) For example, more than 1.5” of rain fell on/about June 12 and the probe readings the following day show saturation using the measurement Kpa.

This chart shows how much water has fallen (blue bars), by date (across the bottom), and corresponding moisture probe readings (from the top.) For example, more than 1.5” of rain fell on/about June 12 and the probe readings the following day show saturation using the measurement Kpa.

Kpa represents the suction required to pull water to the plant. When there is plenty of water in the soil, it is like a very thin milkshake and it is easy to pull the water to the plant. However, when the soil is dry, the water is like a very thick milkshake, making it difficult to pull the water to the plant and therefore requiring greater suction.